At the End of the Civil War Which Reconstruction Plan Was Meant to Go Easy on the South

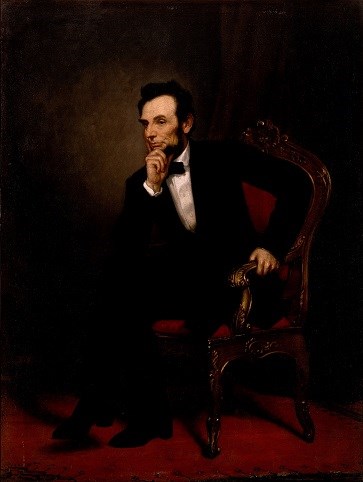

NPS Image

Reconstruction or Restoration?

Following the Union victory in the Civil War, the nation faced the uncertainty of what would happen next. Two major questions arose. Were the Confederate states still part of the Union, or, by seceding, did they need to reapply for statehood with new standards for admission?

Andrew Johnson's view, as stated above, was that the war had been fought to preserve the Union. He formulated a lenient plan, based on Lincoln's earlier 10% plan, to allow the Southern states to begin holding elections and sending representatives back to Washington.

His amnesty proclamations, however, emboldened former Confederate leaders to regain their former seats of power in local and national governments, fueling tensions with freedmen in the South and Republican lawmakers in the North.

NPS Image

Altogether, several variations of Reconstruction arose:

The Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction, or Lincoln's Ten Percent Plan

As Union troops took control of areas of the South, Lincoln implemented this war-time measure to re-establish state governments. It was put forth in hopes that it would give incentive to shorten the war and strengthen his emancipation goals, since it promised to protect private property, not including slaves.

At its core, the plan stated that when 10% of the 1860 voters from a state had taken an oath of allegiance to the U.S. and pledged to abide by emancipation, voters could then elect delegates to draft new state constitutions and establish state governments. Most Southerners, excepting high-ranking Confederate army officers and government officials, would be granted a full pardon.

This plan would serve as a platform for whatever post-war reconstruction would be developed.

The Wade-Davis Agreement, or Congress's Response to the Ten Percent Plan

Congress felt that Lincoln's measures would allow the South to maintain life as it had before the war. Their measure required a majority in former Confederate states to take an Ironclad Oath, which essentially said that they had never in the past supported the Confederacy. The bill passed both houses of Congress on July 2, 1864, but Lincoln pocket vetoed it, and it never took effect.

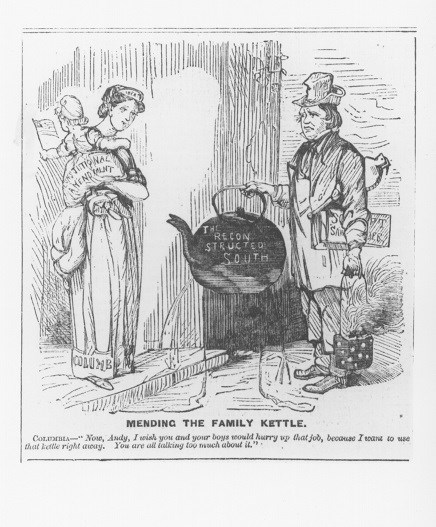

NPS Image

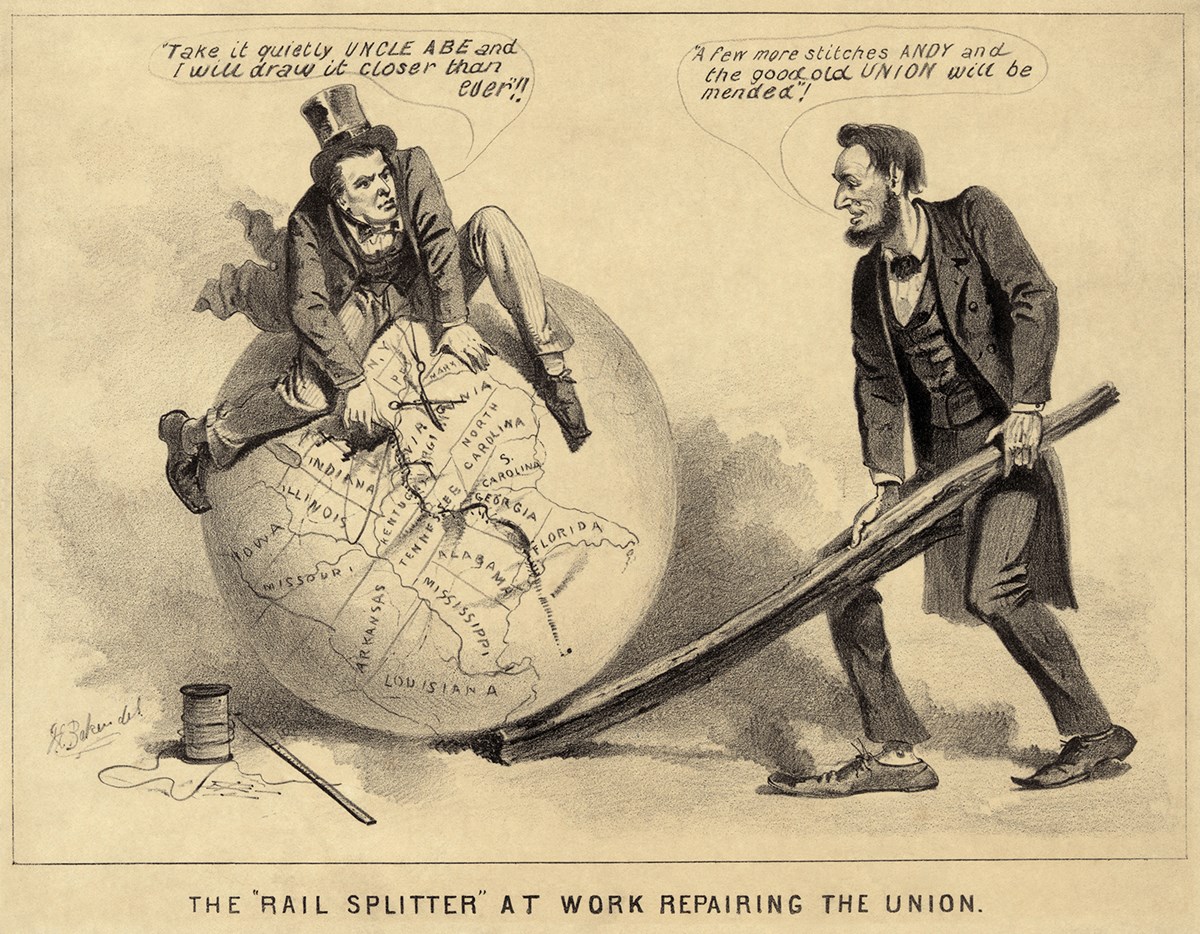

NPS Image

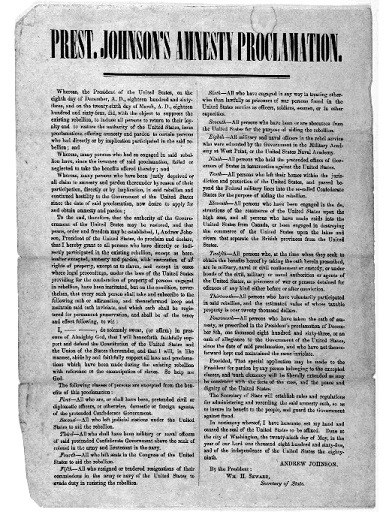

Presidential "Restoration," or Andrew Johnson's Plan for Reconstruction

Following Abraham Lincoln's death, President Andrew Johnson based his reconstruction plan on Lincoln's earlier measure. Johnson's plan also called for loyalty from ten percent of the men who had voted in the 1860 election. In addition, the plan called for granting amnesty and returning people's property if they pledged to be loyal to the United States. The Confederate states would be Under the plan, Confederate leaders would

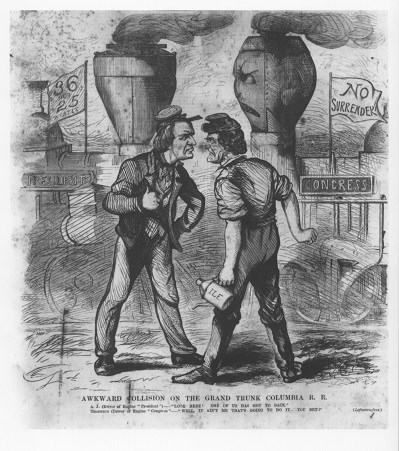

A.J. (Driver of Engine "President") - "Look here! One of us has got to back!"

Thaddeus (Driver of Engine "Congress") - "Well it ain't me that's going to do it! You bet!"

NPS Image

Congressional Reconstruction, or the Military Reconstruction Acts

Passed on March 2nd, 1867, the first Military Reconstruction Act divided the ex-Confederate states into five military districts and placed them under martial law with Union Generals governing. The act also directed that former Southern states seeking to reenter the Union must ratify the 14th Amendment to the Constitution to be considered for readmission. The 14th Amendment granted individuals born in the United States their citizenship, including nearly 4 million freedmen.

The amendment specifically disenfranchised ex-Confederates, barring them from the ballot box. The Constitution states, "Whoever, owing allegiance to the United States, levies war against them or adheres to their enemies, giving them aid and comfort within the United States or elsewhere, is guilty of treason." At the time, their actions were viewed as treasonous. The Confederate States of America's leadership lost their right to vote because they lost their citizenship by committing treason.

The Military Reconstruction Act also protected the voting rights and physical safety of African Americans exercising their rights as citizens of the United States.

The Outc ome

Andrew Johnson and Congress were unable to agree on a plan for restoring the ravaged country following the Civil War. There was a marked difference between Congressional Reconstruction - outlined in the first, second, and third Military Reconstruction Acts - and Andrew Johnson's plan for Presidential Restoration (North Carolina's plan shown here).

In the midst of it all was the human aspect.

The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, often referred to as the Freedmen's Bureau, was established by the War Department on March 3rd, 1865. The Bureau supervised relief and educational activities for refugees and freedmen, including issuance of food, clothing, and medicine. The Bureau also assumed custody of confiscated lands or property in the former Confederate States, border states, District of Columbia, and Indian Territory.

Backlash occurred in the South in the form of the Black Codes. Passed in 1865 and 1866 in Southern states after the Civil War, these Codes severely restricted the new-found freedoms of the formerly enslaved people, and it forced them to work for low or no wages.

Crippling poverty, vast wealth, rampant rumors, fear of insurrection on all levels, assassination, trials - this was the country that all three branches of the Federal government inherited after the war.

The Congressional Plan of Reconstruction was ultimately adopted, and it did not officially end until 1877, when Union troops were pulled out of the South. This withdrawal caused a reversal of many of the tenuous advances made in equality, and many of the issues surrounding Reconstruction are still a part of society today.

dasilvaplimparthid.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.nps.gov/anjo/andrew-johnson-and-reconstruction.htm

0 Response to "At the End of the Civil War Which Reconstruction Plan Was Meant to Go Easy on the South"

Post a Comment