Guy That Went to Calarts and Art Got Worse

Sunstroked and Rigorous: Some Notes on CalArts

• Andrew BerardiniMy car peeled off the freeway on 1 of the last exits before the five climbs into the treacherous Grapevine and through the dull fields and cow factories of the Central Valley en route to Sacramento. Surface roads as fast and wide as highways ribbon out from the freeway and banking company in housing tracts walled with cinderblock and striped by light-green lawns. Squinting past the stucco McMansions and strip malls, I can almost come across the Quondam West movie sets with cowboys hoofing through the scrub below those chocolate mountains; this is the northern hinterland of Los Angeles Canton. At that place, the California Constitute of the Arts (nicknamed CalArts) perches on a hill, weird every bit ever, higher up the recent suburbs metastasizing through the Santa Clarita Valley.

Walt Disney dreamed up this gesamtkunstwerk of a school; the Mouseketeer's American Bauhaus was built on land not far from his picture show ranch. CalArts has since gained a reputation as being conceptually rigorous and morally decadent. A sunstroked yr-round summertime camp backboned with art world savviness, it is a model that went on to exist mimicked past all its successor institutions around Los Angeles. CalArts students met early success in a crew of artists that came to be known every bit the CalArts Mafia in New York (documented in Richard Hertz's Jack Goldstein and the CalArts Mafia, 2004). I of the legends of contemporary art in LA is that the almost ambitious artists all left for New York until Mike Kelley stayed subsequently graduating with an MFA in 1978.

Amidst all the dancers, artists, writers, filmmakers, actors, composers, choreographers, theater-makers and musicians the school notwithstanding produces some of the most successful animators in the world, many of whom even now go to work for Uncle Walt. Each of the various schools (art, dance, music, theater, film/video, disquisitional studies) has developed its own idiosyncratic personality over the years, but all of them endeavor toward some version of an avant-garde or the more advertorial: "cutting-edge." The Plant'south tedious migrate away from its vanguard origins into a more corporate institution troubles the long-term kinesthesia and many of the students, a state of affairs resulting from new accreditation rules, depression revenue outside of tuition, a couple concern-minded by presidents, and the bellboy bureaucracies behind all the to a higher place.

When the school opened its doors in 1970, classes were offered in "Witchcraft" and "Jointrolling" with nary grades or curricula. A sociologist on staff held an "unscheduled class" that took place whenever he happened to run into a educatee on campus. Now, curricula is required and though couched in terms ranging from Loftier Pass to No Pass, the grades fool no ane with their easy correspondence to the old A through F. The nearly conservatizing strength of all however is the sticker toll: $41,700 for enrollment in 2014–2015, not including room, board, or materials—plenty to make a life in the arts more similar mortgaging a house than la vie bohème.

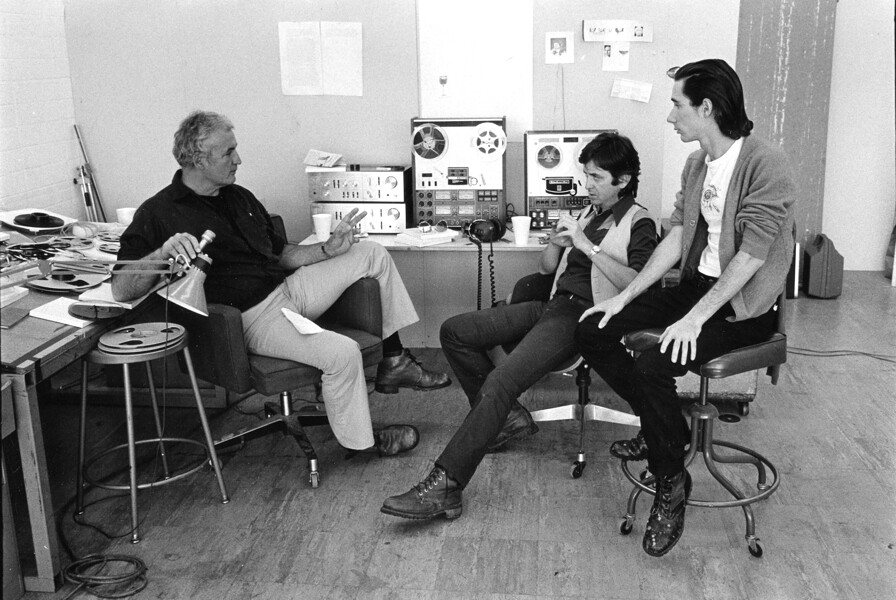

Founding faculty member John Baldessari spoke with critic Christopher Knight in 1992 for the Archives of American Art about his first experiences with the school: "I think every crazy in the earth descended the first year." Recalling some of the early debates, he continued:

"Well, the whole thought was to raise the question what exercise yous practise in an art school? And you say, 'Well, what courses are necessary to teach?' and that question is begging in a way, because you can say, 'Well, can art exist taught at all?' And, y'all know, I prefer to say, 'No, it can't. It can't exist taught.' You can gear up upwardly a situation where art might happen, merely I think that's the closest you get."

The CalArts School of Art owes a lot of its personality to early on teachers like Baldessari too equally Allan Kaprow, Michael Asher, Miriam Schapiro, and Judy Chicago. Though there just briefly, Kaprow was the outset of many Fluxus cohorts recruited by the first dean of art, Paul Brach, and the permissive playfulness of that move still haunts the hallways as does Baldessari's dry humor and fine art world hustle, Asher's hardheaded rigor, and Schapiro and Chicago'south political awareness.

In 1980, Catherine Lord became dean of the School of Art and contentiously skewed the programme into a more progressively political atmosphere that emphasized critical theory. Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe was pushed out in 1986 (after condign the graduate chair at Art Centre in Pasadena), leading to Baldessari splitting mid-year with a Guggenheim in hand, though he too eventually returned to teaching at UCLA.

With the departure of Catherine Lord in 1990, the school hired painter and writer Tom Lawson to accept over as dean, a position he still holds. "Philosophically, Catherine had express interest in actual, physical art-making. She was actually very conceptual, interested in anti-institutional and anti-material critique and promoted that," said Lawson when I recently interviewed him. "When I arrived the product facilities were in really bad shape. I spent quite a scrap of time in my first years rebuilding the physical structures."

The political bent of the program introduced early on and enforced by Lord softened without disappearing under Lawson. New faculty is chosen collectively by one-time kinesthesia, emphasizing the nonhierarchical nature of the school, invariably coming with all the messiness of consensus and committee conclusion-making only also some continuity. (Likewise, the visiting artists lecture series is collectively run past the students.)

When I asked Lawson what made CalArts different, he mentioned the day of interviews the kinesthesia conducts with MFA candidates in mid-March: "The lesser-line question is: Why should I recall of coming here instead of some other place that I've been accustomed? Overall, nosotros really are pretty intellectual as a grouping. Nosotros're all driven by intellectual ideas of where fine art comes from, rather than emotional ones, rather than intuitive ones. That's the caliber of conversation. Nosotros want the students to clear their thinking."

Debate and give-and-take, and thus the ability to clearly articulate a position are at the center of what it ways to be a student at CalArts. This is seen nowhere better than in the crit, a linchpin of modernistic art schoolhouse that consists of one student artist property upward work for the commonage critique of their peers. The late Michael Asher's Mail-Studio taught at CalArts, and featured in Sarah Thornton's Seven Days in the Art World (2008), stands as a monument of the course.

Crits, Studio Visits and Openings

Passing through the forepart doors of CalArts, there'southward a toilet with some photocopied dollar bills hanging on its lip and a sign that reads "Insert Tuition Here." Nearby, a gutted lady mannequin sits skirted and scarved, her plasticine face spooky and realistic. Across from her, a handful of dancers in leotards and stretch-pants bend and look on the tile in front end of a theater. The main hall opens up to a second story lined with studio doors. On the basis floor, I laissez passer a dozen students practicing yoga. Upwardly the stairs and past all the undergrad workspaces, later on a left at the Lime and Mint Galleries and down another hallway, I arrive at one of the less appealing pupil spaces at CalArts known as A402.

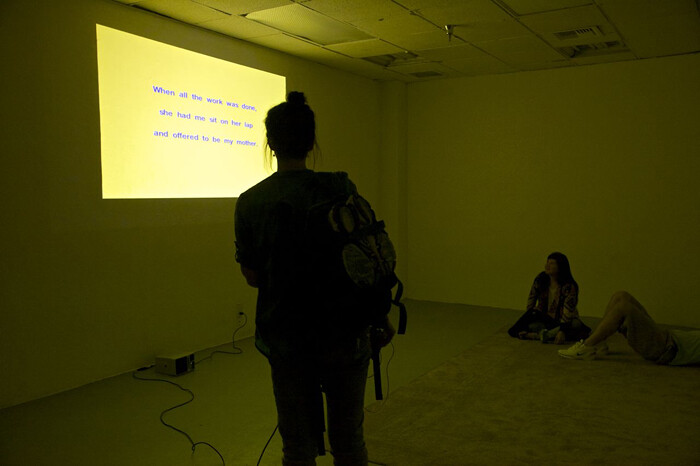

Beneath office console ceilings and fluorescent lights mercifully turned off, the assembled artists sit down on a cool, gray concrete flooring. Leaning confronting pocked and windowless drywall that bears the scars of hundreds of their predecessors, they encircle a lonesome microphone in front of a unmarried-channel projection. A project on the wall reads: "I have so much to do today, but all I want to do is smoke weed and watch Audrey Hepburn cry." These vignettes lasting onscreen from 10 seconds to a couple minutes flash across brilliant, solid color backgrounds, the highlighted words recounting short tales of hot tubs and lost religion, ballgame and meth habit—just funny.The words colour along like karaoke, just the room is silent. One by one nevertheless, the braver students go upwards to the microphone. Some read tiresome and haltingly, some stumble, others enunciate with the unhurried tenderness of reading to a child. Occasionally the comic timing is on, or off, and so that everyone giggles in the dark. At least a fifth of the students quietly nibble sandwiches or sip coffee. Some lie on the floor fully splayed. Thirty-3 stories loop over nearly an hour, all generated from an anonymous online call for submissions, edited only lightly for brevity and clarity. After a brief silence, they showtime grilling the artist, Adriana Baltazar, on meaning. "In that location's something about timing that'south really fucked up here, information technology makes me want to talk like a robot," says an creative person in a vinyl fetish pinnacle and Medico Martens, opening the critique of her peer while petting a docile and desert-colored dog. "Sort of deadpan, similar mumblecore" she adds. (CalArts is a vigorously domestic dog-friendly campus.)

The presiding professor for "AR251: Reconsiderations: Critique Seminar," Charles Gaines, sits on the basis against the wall with his students, adding challenging bon mots, gentle prods, genuine encouragement, Socratic questions, and gnomic wisdom. "It's not performative work without operation, like reading a Bach cantata without playing it. Maybe there's a infinite between the gallery and social media, but I'm nevertheless not sure how that works." A long and meandering conversation nigh social media follows his pronouncement, drifting further and further into itself. Finally, an exasperated beau declares: "Is anyone else confused about why nosotros're talking about social media?" And and so a discussion about the meaning of that. Many variations of the discussion "critical" are employed. "Rigor" is operative also. Someone utters "the commodification of subjectivity." Walter Benjamin is cited.

"Are we all up to appointment on Benjamin?" asks Gaines. A limp, schoolish 'yes' sort of moans out of the artists. The dog's panting punctuates the conversation in its intermittent silences. The girl in the headscarf side by side to me disco-naps.

"The critique of commodity capital is a skilful i," Gaines throws in. "It may be true that our desires are exploited because we are and so consumed by them. Information technology begs the question of how value is exchanged." Gaines frames his commentary with a mail service-Marxist, theoretical language that guides the discussion and is repeated by the students to each other with varying degrees of believability.

I move on to my first scheduled studio visit, meeting second year MFA educatee Meghan Gordon at her bar. Gordon began some times in her own studio (which the neon sign in the narrow studio window advertises). It's tucked down a cement walkway alongside eucalyptus trees in the Broad Studio Buildings at the border of campus. One of 34 grad students in the Schoolhouse of Art (with 15 more in Photography and another 5 in Fine art & Technology), Gordon's manifold practice is an impressive conglomeration of social organizing. In improver to the bar, she hosts an informal lecture/dinner series chosen In-due north out, co-directs an unofficial residency programme at the Establish called locksmith, Inn, and is a member of neverhitsend, described in her bio as "a collective performatively researching communications ideology."

Sitting downwardly at the bar, Gordon pours me a glass of whiskey and opens her laptop. A absurd breeze blows in from the small courtyard through the open door. She plays a video cut into 3 sections that was installed in a recent evidence on campus. One panel plays a video feed of her adult brother expertly playing a video game—an activity that makes watching him a pastime for a group of enthusiasts who comment on the game equally he plays in another panel. Below that is a video of his sister as she sits at a bar, drinking beers, talking to her brother while inviting random strangers from the bar into the video's frame. The video game commenters eventually become concerned and urge her blood brother to turn off the game and really talk to her.

Chop-chop finishing our drinks, Gordon walks me to my next studio visit with Becca Lieb, who has an exhibition in the main edifice—and one of the all-time of the galleries—D301. Hushed in darkness, the capacious space included items whose names reveal their nationality: French Ivory, Irish Bound, forth with a supine candle of the Venus of Willendorf (sticker-priced $12.99) and a neon replica of Rush Limbaugh'due south signature. Also included is an e-mail of verse auto-sent to anyone who wrote her while the show was upwardly. Titled "Out-of-Orifice," it is a haunting poem composed largely of words used by United states intelligence searchbots to flag correspondence for closer examination.

Afterwards some other as well brief half-hour, Lieb takes me to the studio of Laura Schawelka. A graduate of the Städelschule before moving to California, Schawelka's studio is tucked into a bigger, windowless building with hallways smeared with pigment and bathrooms with crossed out and reversed gender signs. Greeting me when I come up into her studio is a sultry, life-sized Miss March 1960, Sally Sarell. A shapely blonde with pants covered in paint, she stands adjacent to her easel, her smock peeling off to reveal what all the women of Playboy are hired to reveal. She'south just one of a series of ladies that Playboy depicted as an artist in their centerfolds, all of which Schawelka'south collected. She sits me down at a laptop to evidence me videos, pictures of pictures, and seductive consumer goods framed in the sexiest means possible. The videos and photographs are spare and sensuous, self-consciously so, imbued with a disquisitional sense that keeps them arms-length abroad from each product'southward allure.

A calendar week after my studio visits, I return for the Thursday nighttime openings. The security guard waves me in and I wander into the crush of idling students, clutching cans of cheap beer and plastic cups in their hands. Though debatable whether it can sincerely teach a human to exist an artist, art schoolhouse tin can certainly teach a educatee how to act like one and the weekly openings are a dry out-run for the decades of receptions artists volition slog through in their lives, the brands of inexpensive beer and cheaper wine rarely irresolute. I head upstairs for Leander Schwazer's opening in the Mint Gallery, who just got back from installing his solo evidence at Museion in Bolzano, Italy—an exhibition I penned a brusque text for. The spirit is collegial and Schwazer hands out sharp fiddling jacks of metal used past the police to popular tires, dozens of which are also embedded in the canvases on the wall.

I continue on, stumbling into a handful of performances. Among them: a live-action experimental animation and a couple playing a pianoforte outdoors in the dark. Drifting back through the warren of windowless corridors that intersect the main edifice, I terminate in at some times—the courtyard out front swells with students clambering in and out of the bar, an epic dance party. Competing music from carve up shindigs shimmies through open studio doors. Under cold fluorescent white light, two unshaven men vigorously argue, jabbing the air with paw-rolled cigarettes, their voices carrying over the Talking Heads vocal, "Once in a Lifetime." In another, bathed in a red glow, a man shakes his head stiffly left and right to an entirely different crush than the woman wildly swinging her hips and punching the air, though both ostensibly moving to the honeyed funk of James Brown. With each night closer to graduation, when this heavily mortgaged utopia graduates its masters, the parties get after and become more than frenzied. Their oscillating beats blare entirely unheard from the wide cobblestone area of McBean Parkway. Outside the campus, in not bad suburban houses, dark except for the sodium orange glow of streetlamps, the citizenry sleep, resting for piece of work early on the adjacent morning.

—Andrew Berardini

Andrew Berardini is a writer in Los Angeles. He is a recent recipient of the Andy Warhol/Artistic Capital Grant for Art Writers. His forthcoming volume about Danh Vō and relics volition be released past Mousse.

dasilvaplimparthid.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.artandeducation.net/schoolwatch/58005/sunstroked-and-rigorous-some-notes-on-calarts

0 Response to "Guy That Went to Calarts and Art Got Worse"

Post a Comment